‘The absence of conscription in Ireland leaves it open to young Irish practitioners to profit by the military service of English, Scottish and Welsh doctors and set up practice in the homes of the absentees to their obvious hurt. How does the British Medical Association hope to deal with that? Nay, to put it more fairly, how can we hope that the British Medical Association can right this wrong?’

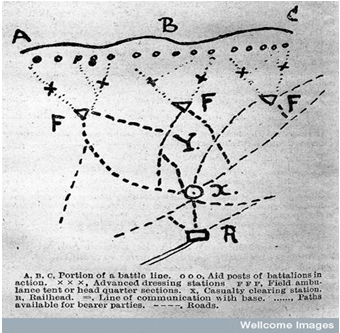

Portion of a battle line, outlining casualty clearing stations

Source: Wellcome Images, L0027194, Wellcome Library

On 18 August 1914, the first contingents of Irish medical personnel travelled to France; No.1 Stationary Hospital, No.1 General Hospital and No.13, 14, and 15 Field Ambulance Divisions departed Dublin for Le Havre. On the same date, No. 16 and 17 Field Ambulances departed Cork for Saint-Nazaire. Initial reactions to the wartime setup varied among the contingent depending on their assignment. In 1914, RAMC Command implemented an intricate casualty clearing process on the Western Front. Significant numbers of medical personnel occupied the roles at each stage of this process and Irish physicians and surgeons were among them. Stretcher-bearers collected injured soldiers from the combat zone and carried them to the nearest Regimental Aid Post – a zone occupied by RAMC MOs, normally located in shell craters or building ruins – before transporting the wounded to Advanced Dressing Stations. Here, injured soldiers had their wounds dressed and were then transported via Field Ambulance – horse-drawn carriages or motor vehicles – to a Casualty Clearing Station (CCS). RAMC medical personnel in the CCS dealt with injuries requiring immediate treatment and conducted numerous surgical procedures. Ambulance cars and trains then transported the wounded, fit for transportation, to nearby hospitals established by the RAMC or voluntary groups, like the Red Cross. Hospitals were located close to battlefields. MOs also identified wounded men better suited to treatment in hospitals on the home-front and recommended these men be moved, via hospital ship, back to domestic hospitals in Britain and Ireland.

Photograph showing a ward, with patients either in bed or on chairs, c.1915

Source: Wellcome Images, L0060826, Wellcome Library

The majority of hospital ships arriving in Ireland docked in Dublin and contained an average of 400 soldiers. From 1914 to 1918, approximately 70 institutions located throughout Ireland provided facilities for the treatment of 16,000 returning sick and wounded. These included auxiliary wards and hospitals and a number of specialist institutions established by RAMC Command (Ireland) for the treatment of specific diseases. In 1915, for example, the War Office appointed Lieutenant-Colonel William Dawson, Inspector of Lunatic Asylums in Ireland, as RAMC (Ireland) specialist in nerve diseases. On 16 June 1916, Dawson took charge of the Richmond War Hospital, located in Dublin’s Grangegorman Asylum. The Richmond War Hospital catered for 32 soldiers suffering from mental disorders. From the date of opening till its closing on 23 December 1919, the Richmond War Hospital treated 362 cases, of which two-thirds were discharged to friends or ordinary military hospitals, two returned to duty and 31 sent directly to civil asylums. While the institution was helpful in the RAMC’s attempts to provide treatment for mental cases, it was undeniably small. Therefore, in October 1916, the War Office requested Dawson to facilitate them by placing an asylum with 500 beds at the disposal of the RAMC. Similar arrangements had been managed successfully in Britain. In Ireland the vastly overcrowded asylums made this an unlikely prospect. Yet, in April 1917, the War Office acquired Belfast’s Civil Lunatic Asylum and incorporated it as part of the Belfast War Hospital. The hospital received Irish men suffering from mental illness during active service and also treated men, not of Irish birth, who belonged to Irish regiments. The first military cases arrived on 15 May 1917. Staff consisted of men who had enlisted in the RAMC for the duration of the war and who had previous experience working in asylums. Between the opening of the hospital and its closing on 15 December 1919, 1,193 cases were admitted; 772 were discharged into the care of their family or friends and 103 transferred to other hospitals more suited to their treatment needs.

This post has given a brief overview of Irish medical involvement in the First World War and using the small example of Irish asylums, has highlighted the impact of the conflict on Irish medical infrastructure. In future pieces, I will profile some of the Irish doctors who participated in the First World War and, using details gathered from diaries and letters, detail their roles and experiences on various fronts. As a PhD student researching Irish medical personnel in the First World War, I am always pleased to be contacted with details of new source material. If you are in possession of diaries, letters or postcards of Irish medical personnel who participated in the First World War, please get in touch – David “dot” Durnin “at” ucd.ie

David Durnin is an Irish Research Council Doctoral Scholar, at the Centre for the History of Medicine in Ireland, University College Dublin. For more information on his research, click here.

.jpg)

.jpg)